Giotto di Bondone (1267 – 1337) or Giotto was born at Colle di Vespignano in the Mugello valley near Florence (Girardi 8). He studied under the Florentine painter Cenni di Pepo Cimabue (1240 – 1302), and was influenced by sculptor and architect Arnolfo di Cambio (1240 – 1300) (Girardi 16). “Giotto’s art represents a landmark in a new era because it introduced a natural and lifelike style that anticipated Italian Renaissance picture-making” (Fiero 180).

Giotto’s greatest masterpieces are the frescos he painted inside the Arena or Scrovegni Chapel located in Padua, a city 30 miles southwest of Venice, Italy. Enrico Scrovegni commissioned the Chapel in 1300.  Enrico’s father, Riginaldo Scrovegni, accumulated a large amount of wealth lending money at usurious rates, contrary to the catholic virtue of charity. It is believed that Enrico commissioned the Chapel to expiate his father’s sins and to provide a fitting burial place for members of his family. It was dedicated to St. Mary of Charity in 1305. The Chapel is often referred to as the Arena Chapel because of its close proximity to a former Roman amphitheatre (Kloss 40-41).

Enrico’s father, Riginaldo Scrovegni, accumulated a large amount of wealth lending money at usurious rates, contrary to the catholic virtue of charity. It is believed that Enrico commissioned the Chapel to expiate his father’s sins and to provide a fitting burial place for members of his family. It was dedicated to St. Mary of Charity in 1305. The Chapel is often referred to as the Arena Chapel because of its close proximity to a former Roman amphitheatre (Kloss 40-41).

The Chapel has six windows located on the right side as you enter the Chapel. The Scrovegni Palace was originally located on the left side of the building therefore no windows were constructed on that side of the Chapel. The Chapel is in the shape of a rectangle with a barrel-vaulted ceiling and the walls are covered with plaster. Unlike most Gothic style churches, it has no ribs, moldings, cornices or pilasters. The design of the Chapel lent itself to Giotto’s artwork because of it large flat uninterrupted surfaces (Eimerl 112).

Giotto painted his artwork on the walls and ceiling of the Chapel using the fresco method in which water based colors are painted onto wet plaster. Painting onto wet plaster allows the paint to be infused into the plaster creating a very durable artwork. However, since the painter must stop when the plaster dries it requires the artist to work quickly and flawlessly (Kloss 41).

Giotto’s paintings inside the Chapel can be divided into three sections: ceiling, top portion of the sidewalls and the front and back walls, and the bottom portion of the sidewalls.  All of the scenes on the sidewalls are separated from each other by faux marble banding.

All of the scenes on the sidewalls are separated from each other by faux marble banding.

I. Ceiling: The ceiling is painted in cobalt blue to give the appearance of the sky with ten medallion shaped portraits of Christ, St. John the Baptist, The Virgin and Child, Baruch, Isaiah, Daniel, Malachi and 3 unidentified prophets (Eimerl 116).

II. Top Portion of the Side Walls and the Front and Back Walls: These walls are composed of thirty-nine narrative scenes. The scenes on the sidewalls can be further divided into three tiers and the scenes appear in chronological order. The top tier is the life of Mary and her parents, Joachim and Anne. The six scenes on the right wall are events prior to Mary’s birth and include:

- The Expulsion of Joachim from the Temple,

- Joachim Retires to the Sheepfold,

- The Annunciation to Anne,

- The Sacrifice of Joachim,

- The Vision of Joachim, and

- The Meeting at the Golden Gate.

The top tier continues on the left wall from back to front with scenes from Mary’s life prior to the birth of Jesus and includes:

- The Birth of the Virgin,

- The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple,

- The Presentation of the Rods,

- The Watching of the Rods,

- The Betrothal of the Virgin, and

- The Virgin’s Return Home.

The first tier ends at the front wall with God the Father sending the Angel Gabriel to deliver his message to Mary. Beneath this scene is the Annunciation to Mary. On the left side of the round arch that leads into the sanctuary is the Angel Gabriel delivering Gods message, and on the right side of the arch is Mary receiving his message.

The middle tier continues the chronology of events beginning on the front wall beneath the scene of Mary receiving the annunciation with The Visitation. The tier continues on the right wall with the life of Jesus before his public ministry and includes:

- The Nativity,

- The Adoration of the Magi,

- The Presentation of Christ in the Temple,

- The Flight into Egypt, and

- The Massacre of the Innocents.

The middle tier continues on the left wall with scenes from his public ministry prior to his passion, and include:

- Christ Arguing with the Elders,

- The Baptism of Christ,

- The Marriage at Cana,

- The Raising of Lazarus,

- The Entry into Jerusalem, and

- The Expulsion of the Merchants from the Temple.

The middle tier’s final scene is on the front wall, under the Angel Gabriel, and depicts The Pact of Judas.

The bottom tier begins on the front right wall with:

- The Last Supper,

- The Washing of the Feet,

- The Kiss of Judas,

- Christ before Caiaphas, and

- The Mocking of Christ.

The bottom tier continues on the left wall from back to front with:

- The Road to Calvary,

- The Crucifixion,

- The Lamentation (Pieta),

- The Angel at the Tomb (Noli Me Tangere),

- The Ascension, and

- Pentecost.

The final scene, The Last Judgment, is on the back wall (Eimerl 112-129).

III. Bottom Portion of the Side Walls: The bottom portion of the sidewalls contains 14 scenes. The seven scenes on the right wall depict the seven heavenly virtues of prudence, fortitude, temperance, justice, faith, charity, and hope. The seven scenes on the left wall depict the seven vices of despair, envy, infidelity, injustice, wrath, inconstancy, and folly (Cole 70).

“Giotto broke with the decorative formality of Byzantine painting …. In place of the flat stylized saints of the Byzantine icon, he … gave his figures a three-dimensional presence [and] brought a new realism to his paintings” (Fiero 180). This new realism and his depiction of humanism are dramatically expressed in the Lamentation.  In the background of this scene, a ridge of rock points our attention to the face of Christ. His head held in the lap of his grief stricken mother, Mary “… their two haloed heads in intense juxtaposition, a concentration of tenderness and sorrow” (Kloss 52). “This is not only the Virgin and Christ but a very human mother and son” (Cole 91). On the top of the ridge is a barren tree symbolizing both death and the hope of rebirth. In the blue sky above Jesus are ten angels who stare down with great anguish on their faces. Holding Christ’s limp arms is Martha, and her sister Mary Magdalene holds his feet. Behind them is St. John who throws back his arms, and to the right stands Joseph of Arimathaea and Nicodemus. On the left stands a group additional mourners, and seated in front of Christ’s body are two individuals who sit with their backs to us staring at his body (Cole 90-91). “… The pictorial representation of great loss and grief in this fresco has never been surpassed” (Kloss 52). Giotto’s new style of showing true human emotion in a realistic way became the precursor for the Italian Renaissance art that followed.

In the background of this scene, a ridge of rock points our attention to the face of Christ. His head held in the lap of his grief stricken mother, Mary “… their two haloed heads in intense juxtaposition, a concentration of tenderness and sorrow” (Kloss 52). “This is not only the Virgin and Christ but a very human mother and son” (Cole 91). On the top of the ridge is a barren tree symbolizing both death and the hope of rebirth. In the blue sky above Jesus are ten angels who stare down with great anguish on their faces. Holding Christ’s limp arms is Martha, and her sister Mary Magdalene holds his feet. Behind them is St. John who throws back his arms, and to the right stands Joseph of Arimathaea and Nicodemus. On the left stands a group additional mourners, and seated in front of Christ’s body are two individuals who sit with their backs to us staring at his body (Cole 90-91). “… The pictorial representation of great loss and grief in this fresco has never been surpassed” (Kloss 52). Giotto’s new style of showing true human emotion in a realistic way became the precursor for the Italian Renaissance art that followed.

Works Cited

Battisti, Eugenio. Giotto. Trans. James Emmons. Cleveland: World Publishing, 1960. Print.

Cole, Bruce, and Eugenio. Giotto and Florentine Painting 1280 – 1375. New York: Harper & Row, 1976. Print.

Crenshaw, Paul, Rebecca Tucker, and Alexandra Bonfante-Warren. Discovering the Great Masters – the Art Lover’s Guide to Understanding Symbols in Painting. New York: Universe, 2009. Print.

Eimerl, Sarel. The World of Giotto. New York: Time, 1967. Print.

Fiero, Gloria K. Landmarks in Humanities. 2nd ed. 2006. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009. Print.

Girardi, Monica. Giotto the Founder of Renaissance Art – His Life in Paintings. Ed. Susannah Steel. Trans. Anna Bennett. 1999. New York: DK, 1999. Print.

Kloss, William. A History of European Art. Chantilly: Teaching Company, 2005. Print.

Stokstad, Marilyn. Art History. Ed. Sarah Touborg. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2008. Print.

Zbinden, Hans, ed. Giotto Frescoes. New York: Oxford, 1950. Print.

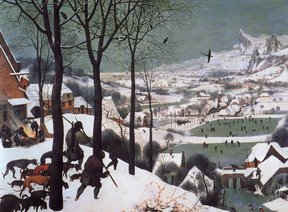

“Like Bosch Brueghel was concerned with Human folly; like Durer, he had traveled to Italy and embraced the Humanism of the Renaissance.” [Fiero 235] His style built on the style of the Limbourg brothers.

“Like Bosch Brueghel was concerned with Human folly; like Durer, he had traveled to Italy and embraced the Humanism of the Renaissance.” [Fiero 235] His style built on the style of the Limbourg brothers. The painting is part of a series depicting different times of the year. Only five of the original six paintings still exist. It is speculated that an additional six paintings in the series likely existed.

The painting is part of a series depicting different times of the year. Only five of the original six paintings still exist. It is speculated that an additional six paintings in the series likely existed.